How to Safely Return to Running After an Injury is a topic that resonates deeply with many athletes who have faced the disappointment of an enforced break from their passion. This guide aims to transform that setback into a strategic comeback, offering a clear roadmap for recovery and a renewed sense of confidence on the track or trail. We understand the desire to get back to what you love, and our approach is designed to make that journey not only possible but also remarkably successful.

This comprehensive exploration delves into the critical aspects of resuming your running routine post-injury. We will meticulously cover the importance of understanding the risks associated with premature return, the undeniable benefits of a structured rehabilitation program, and the common pitfalls that can derail progress. Furthermore, we will address the often-overlooked psychological impact of an injury and equip you with the tools to navigate these challenges effectively.

From assessing your physical readiness to developing a personalized, gradual return plan, this guide is your essential companion.

Understanding the Importance of a Safe Return to Running

Returning to running after an injury is a significant milestone, but it’s one that requires careful consideration and a methodical approach. Rushing back into your previous training regimen can undo your hard work and potentially lead to re-injury, prolonging your recovery and impacting your long-term running goals. A well-planned return-to-running program is not just about physical healing; it’s about rebuilding strength, confidence, and a sustainable relationship with the sport.The temptation to get back to pre-injury performance levels quickly is understandable, especially for dedicated runners.

However, this impatience is a common pitfall that can have serious consequences. Understanding the risks and benefits associated with a gradual return is crucial for a successful and lasting recovery.

Potential Risks of Returning to Running Too Soon

Resuming running without adequate healing and conditioning can exacerbate the initial injury or lead to new compensatory injuries. Tissues that are not fully repaired are more susceptible to stress, and the body may adopt altered biomechanics to compensate for lingering pain or weakness, placing undue strain on other areas. This can create a cycle of injury that is difficult to break.Common risks include:

- Re-aggravation of the original injury, leading to a longer recovery period.

- Development of new injuries due to altered gait patterns or compensatory movements.

- Increased inflammation and pain, hindering further training progression.

- Psychological discouragement and loss of motivation due to setbacks.

- Chronic pain or persistent issues that could have been avoided with a patient approach.

Benefits of a Structured and Gradual Return-to-Running Program

A structured return-to-running program is designed to systematically reintroduce your body to the demands of running, minimizing stress while maximizing recovery and adaptation. This approach prioritizes rebuilding the necessary strength, flexibility, and endurance in a controlled manner.The advantages of this methodology are manifold:

- Promotes tissue healing: Allows injured tissues sufficient time to repair and strengthen before being subjected to high impact.

- Reduces risk of re-injury: By gradually increasing mileage and intensity, the body can adapt without overload.

- Restores biomechanical efficiency: Incorporates exercises to correct any lingering gait issues or muscle imbalances.

- Builds confidence: Successfully completing each stage of the program fosters psychological resilience and belief in one’s ability to run again.

- Enhances long-term performance: A strong foundation built during the return phase can lead to improved running form and reduced susceptibility to future injuries.

Common Mistakes Runners Make When Attempting to Resume Training Post-Injury

Despite the best intentions, many runners fall into common traps when trying to get back to their running routine. Awareness of these mistakes can help individuals avoid them.These common errors include:

- Ignoring pain: Pushing through pain is a direct route to re-injury.

- Increasing mileage too quickly: A sudden jump in distance can overwhelm healing tissues.

- Skipping warm-up and cool-down: These essential components prepare the body and aid recovery.

- Neglecting strength and conditioning: Weak supporting muscles can lead to poor form and increased injury risk.

- Returning to previous intensity too soon: Speed work or hills should be introduced very gradually.

- Comparing progress to others: Every runner’s recovery is unique and should not be measured against another’s timeline.

Psychological Aspects of Returning to Running After a Setback

The mental journey of returning to running after an injury is as important as the physical one. Setbacks can erode a runner’s confidence, leading to anxiety, frustration, and even fear of re-injury. It’s crucial to acknowledge and address these psychological challenges.The mental recovery process involves:

- Rebuilding confidence: Celebrating small victories, such as completing a short run without pain, is vital for restoring self-belief.

- Managing fear: Understanding the gradual progression of a return-to-running plan can help alleviate the fear of re-injury.

- Patience and acceptance: Recognizing that recovery takes time and that progress may not be linear is essential for maintaining a positive outlook.

- Focusing on the present: Dwelling on past performance or future goals can be counterproductive; concentrating on the current run and its execution is more beneficial.

- Seeking support: Talking to coaches, therapists, or fellow runners who have experienced similar situations can provide valuable emotional support and perspective.

Assessing Readiness for Return to Running

Returning to your beloved activity of running after an injury requires a thoughtful and deliberate approach. Simply feeling “better” is not always a sufficient indicator of readiness. A comprehensive assessment ensures that your body has adequately healed and is prepared to withstand the demands of running, thereby minimizing the risk of re-injury. This section will guide you through the crucial steps of evaluating your physical preparedness.The process of assessing readiness involves looking for objective signs of healing and functional capacity.

It’s a multi-faceted evaluation that combines your subjective experience with objective measures of your body’s capabilities. By systematically addressing these indicators, you can make an informed decision about when and how to safely reintroduce running into your routine.

Signs of Sufficient Healing

A healed injury typically presents with a reduction in pain and swelling, and a return to normal range of motion. The absence of these acute symptoms is a primary indicator that the healing process is progressing well. It’s important to differentiate between residual soreness and true pain that signals ongoing tissue damage.Key indicators that an injury has sufficiently healed include:

- Absence of sharp or significant pain during daily activities.

- No noticeable swelling or tenderness at the injured site.

- Full, pain-free range of motion in the affected joint and surrounding areas.

- Ability to bear weight and perform basic movements without discomfort.

- No clicking, popping, or grinding sensations during movement that were not present before the injury.

Physical Readiness Indicators for Runners

Before lacing up your running shoes for a full return, it’s vital to ensure your body possesses the strength, stability, and endurance necessary to handle the repetitive impact of running. This involves assessing your muscular strength, balance, and the ability of the injured area to tolerate load.A checklist of physical readiness indicators for a runner to consider includes:

- Strength: The ability to perform single-leg squats, calf raises, and other exercises that mimic running movements without pain or significant weakness.

- Balance: Maintaining balance on the injured leg for at least 30 seconds without swaying or needing to grab for support.

- Proprioception: The body’s awareness of its position in space, which can be tested by performing exercises with eyes closed on the affected leg.

- Endurance: The ability to perform a series of controlled movements, such as hopping or jumping, for a set number of repetitions without pain.

- Functional Movement: Performing exercises like lunges, step-ups, and jogging in place without any signs of pain or compensation.

The Role of Pain Levels and Functional Movement Assessments

Pain is a crucial signal from your body, and its presence or absence during specific movements provides valuable insight into your readiness. It is not simply about avoiding pain, but understanding what kind of pain is acceptable and what is not. Functional movement assessments go beyond simple strength tests, evaluating how your body moves as a unit during activities that simulate running.Pain levels are assessed on a scale, typically from 0 to 10, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain imaginable.

During your assessment, you should aim for a pain level of 0-2 out of 10 during and immediately after specific movements. Any pain above this threshold suggests that the tissues are not yet ready for the stress of running.Functional movement assessments involve observing your form and technique during exercises. For instance, when performing a single-leg squat, a physiotherapist or trainer would look for proper knee alignment, hip control, and core engagement.

Deviations from ideal form, even without significant pain, can indicate underlying weaknesses or imbalances that need to be addressed.

“Listen to your body. Pain is a message, not a challenge to be overcome.”

Self-Assessment Protocol for Evaluating Readiness to Run

You can implement a structured self-assessment protocol to gauge your readiness before attempting to run. This protocol should gradually increase the demands on your body, allowing you to monitor your response.A self-assessment protocol for evaluating readiness to run:

- Phase 1: Basic Movement Assessment (Weeks 1-2 post-symptom resolution)

- Perform gentle range of motion exercises for the injured limb.

- Engage in light strengthening exercises, such as heel raises and calf stretches, focusing on pain-free execution.

- Walk for 20-30 minutes daily, observing for any discomfort.

- Phase 2: Load and Impact Tolerance (Weeks 3-4)

- Introduce single-leg balance exercises for 30 seconds.

- Perform 2-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions of bodyweight squats and lunges, ensuring good form.

- Engage in short periods of jogging in place or on a treadmill for 1-2 minutes, followed by walking breaks. Monitor pain levels closely.

- Phase 3: Gradual Return to Jogging (Weeks 5-6)

- Begin with short jogging intervals (e.g., 1 minute jog, 4 minutes walk) for a total of 20-30 minutes, 2-3 times per week.

- Gradually increase the jogging duration and decrease the walking duration as tolerated, ensuring no increase in pain.

- Incorporate short, controlled hops or skips on the spot to assess plyometric readiness.

- Phase 4: Progressive Running (Weeks 7 onwards)

- If Phase 3 is completed without pain, gradually increase running time by no more than 10% per week.

- Listen to your body and take extra rest days if needed.

- Consider incorporating gentle hill work or fartlek training only when comfortable with consistent running.

Throughout this protocol, maintain a pain log to track your responses. If you experience any significant increase in pain (above 2/10) during or after an exercise, regress to the previous phase or take additional rest days. Consulting with a physical therapist or sports medicine professional is highly recommended to tailor this assessment to your specific injury and needs.

Developing a Gradual Return-to-Running Plan

Returning to running after an injury requires a thoughtful and structured approach to prevent re-injury and ensure long-term success. A gradual plan is crucial for allowing your body to adapt to the increasing demands of running without overwhelming healing tissues. This phased approach helps build strength, endurance, and confidence, making your comeback sustainable and enjoyable.The foundation of a safe return-to-running plan is a progressive reintroduction of running, often starting with walk-run intervals.

This strategy allows your cardiovascular system and musculoskeletal tissues to gradually acclimate to the impact and stress of running. By alternating between walking and running, you manage the load on your body, reducing the risk of setbacks.

Phased Approach with Walk-Run Intervals

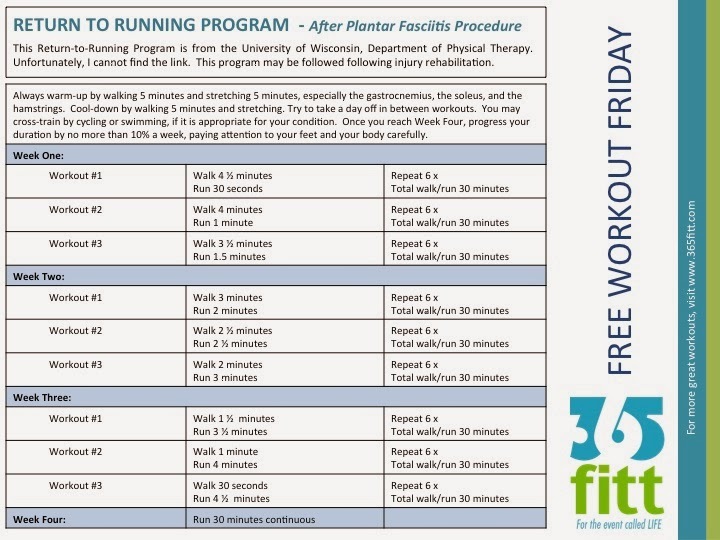

The initial phase of returning to running should focus on building a base through a carefully structured walk-run program. This method is highly effective in reintroducing the biomechanical stresses of running in a controlled manner. It allows for adequate recovery between running bouts, which is essential for tissue repair and adaptation.A typical walk-run progression involves starting with short running intervals interspersed with longer walking periods.

As your body adapts and you experience no pain or discomfort, the duration of the running intervals is gradually increased, and the walking intervals are shortened. This systematic increase in load ensures that your body has sufficient time to respond and strengthen.

Sample Week-by-Week Progression for Initial Return to Running

The following sample progression Artikels a potential path for the first few weeks of returning to running. It’s important to remember that this is a template, and individual progress may vary. Listen to your body and adjust as needed.

Week 1: Foundation Building

- Frequency: 3 days per week, with at least one rest day between sessions.

- Session Structure: Warm-up (5 minutes brisk walking), then repeat 6-8 times: 1 minute running, 4 minutes walking. Cool-down (5 minutes walking).

- Total Time: Approximately 30-40 minutes per session.

Week 2: Increasing Running Duration

- Frequency: 3 days per week.

- Session Structure: Warm-up (5 minutes brisk walking), then repeat 5-7 times: 2 minutes running, 3 minutes walking. Cool-down (5 minutes walking).

- Total Time: Approximately 30-35 minutes per session.

Week 3: Extending Running Intervals

- Frequency: 3 days per week.

- Session Structure: Warm-up (5 minutes brisk walking), then repeat 4-6 times: 3 minutes running, 2 minutes walking. Cool-down (5 minutes walking).

- Total Time: Approximately 25-30 minutes per session.

Week 4: Further Integration of Running

- Frequency: 3 days per week.

- Session Structure: Warm-up (5 minutes brisk walking), then repeat 3-5 times: 5 minutes running, 2 minutes walking. Cool-down (5 minutes walking).

- Total Time: Approximately 25-30 minutes per session.

This progression can continue, gradually increasing the running duration and decreasing the walking duration until you are running continuously for your desired time or distance.

Incorporating Cross-Training and Strength Exercises

While the focus is on returning to running, a comprehensive plan also includes cross-training and targeted strength exercises. Cross-training activities, such as swimming, cycling, or elliptical training, can help maintain cardiovascular fitness without the impact of running. These activities engage different muscle groups and can aid in overall conditioning.Strength training is paramount for injury prevention and rehabilitation. It helps to strengthen the muscles that support running, including the core, hips, glutes, and legs.

Stronger muscles provide better stability, improve running form, and can absorb impact more effectively, reducing the strain on joints and connective tissues.

- Core Strength: Exercises like planks, bird-dogs, and dead bugs are crucial for spinal stability and efficient power transfer during running.

- Hip and Glute Strength: Glute bridges, clamshells, and single-leg squats help to strengthen the muscles responsible for hip extension and stabilization, vital for preventing common running injuries.

- Lower Leg Strength: Calf raises and eccentric heel drops can improve the strength and resilience of the calf muscles and Achilles tendon.

It is advisable to perform strength training 2-3 times per week, ideally on non-running days or after an easy run, to allow for adequate recovery.

Strategies for Listening to Your Body and Adjusting the Plan

The most critical component of a safe return-to-running plan is the ability to listen to your body and make necessary adjustments. Pain is a signal that something is not right, and pushing through it can lead to re-injury. Understanding the difference between normal muscle fatigue and injury-related pain is key.

Key Indicators to Monitor:

- Pain: Differentiate between mild muscle soreness and sharp, persistent, or localized pain. Any sharp or increasing pain during or after running should be a sign to stop or reduce intensity.

- Stiffness: While some stiffness is normal, significant or prolonged stiffness that hinders movement or increases with activity warrants attention.

- Fatigue: Excessive fatigue that doesn’t resolve with rest may indicate overtraining or insufficient recovery.

- Swelling or Redness: These are clear signs of inflammation and require immediate rest and potentially medical evaluation.

If you experience any concerning symptoms, do not hesitate to step back. This might mean reducing the duration of your run, shortening the running intervals, taking an extra rest day, or reverting to an earlier stage of the plan.

“The body speaks, and the wise runner listens.”

Regularly assess how you feel after each run. Keep a training log to track your progress, any discomfort experienced, and how you felt. This log can be invaluable for identifying patterns and making informed decisions about your plan.

Guidance on Duration and Intensity of Early Running Sessions

The duration and intensity of early running sessions should be conservative. The primary goal in the initial stages is not speed or distance, but rather to reintroduce the stress of running in a controlled and pain-free manner.

- Duration: Begin with very short running intervals, as Artikeld in the sample progression. The total time spent running in any single session should be minimal at first. For example, in Week 1, you might only run for a total of 6-8 minutes spread across the session.

- Intensity: Focus on an easy, conversational pace. You should be able to speak in full sentences while running. Avoid any sprinting or high-intensity efforts. The goal is to build aerobic capacity and tissue tolerance, not to test your speed limits.

As you progress through the weeks and your body tolerates the increased load, you can gradually increase the duration of your running intervals and the total running time per session. Intensity can also slowly increase, but always prioritize a pain-free experience. A common guideline is to increase your total weekly mileage by no more than 10% to avoid overloading your system.

However, in the early stages of returning from injury, this guideline might need to be even more conservative, focusing on time rather than distance.

Essential Strength and Conditioning for Injury Prevention

Returning to running after an injury is a critical period that requires more than just gradual mileage increases. A robust strength and conditioning program is paramount to rebuilding the body’s resilience, addressing underlying weaknesses that may have contributed to the initial injury, and preventing future setbacks. This focused approach ensures that your running form is supported by a strong, stable foundation, allowing you to return to your sport with confidence and durability.The goal of strength and conditioning in post-injury rehabilitation is to systematically enhance the muscular support system that underpins your running.

This involves targeting key muscle groups, improving neuromuscular control, and fostering a balanced, resilient physique capable of withstanding the repetitive impact of running. By integrating these exercises, you are not merely recovering; you are actively building a stronger, more injury-resistant runner.

Beneficial Strengthening Exercises for Recovering Runners

Strengthening exercises for runners recovering from injury should focus on rebuilding functional strength, improving endurance in key muscle groups, and addressing any imbalances. These exercises are designed to mimic the demands of running while providing a controlled environment for healing tissues to adapt and strengthen. The emphasis is on proper form and controlled movements rather than lifting heavy weights, especially in the initial stages of recovery.Here are categories of beneficial strengthening exercises:

- Bodyweight Exercises: These are foundational and can be performed anywhere, focusing on control and proper form. Examples include squats, lunges, glute bridges, and calf raises.

- Resistance Band Exercises: Bands offer variable resistance and are excellent for activating and strengthening smaller stabilizing muscles, particularly around the hips and glutes. Exercises like band walks, clam shells, and monster walks are highly effective.

- Light Dumbbell or Kettlebell Exercises: As strength progresses, incorporating light weights can further challenge muscles and build strength. This might include goblet squats, Romanian deadlifts, and single-leg deadlifts.

- Plyometric Exercises (Advanced): Introduced much later in the rehabilitation process and only when cleared by a healthcare professional, these exercises help improve power and explosiveness, crucial for efficient running. Examples include box jumps and jump squats, performed with meticulous attention to landing mechanics.

Core Strengthening Exercises for Improved Stability

A strong core is the bedrock of efficient and safe running. It acts as a central stabilizer, transferring force efficiently between the upper and lower body and preventing excessive movement that can lead to strain and injury. A well-conditioned core contributes to better posture, improved running economy, and reduced risk of lower back pain and other running-related ailments.To enhance core stability, incorporating a variety of exercises that engage the deep abdominal muscles, obliques, and lower back is essential.

These exercises promote proprioception and control, ensuring that your torso remains stable even as your limbs move dynamically during the running stride.Examples of core strengthening exercises include:

- Plank Variations: Standard plank, side plank, and plank with leg or arm lifts engage the entire core musculature. Focus on maintaining a straight line from head to heels, avoiding hip sagging or lifting.

- Bird-Dog: This exercise improves coordination and core stability by extending opposite arm and leg while maintaining a neutral spine.

- Dead Bug: Lying on your back, this exercise involves slowly lowering opposite arm and leg while keeping the lower back pressed into the floor. It’s excellent for challenging the deep abdominal muscles.

- Russian Twists: Performed seated with knees bent, this exercise targets the obliques. Start with no weight or a very light weight, focusing on controlled rotation.

- Glute Bridges: While primarily a glute exercise, glute bridges also engage the core to maintain pelvic stability.

Exercises Targeting Hip and Glute Strength to Support Running Mechanics

The hips and glutes are primary movers and stabilizers during the running gait. Weakness in these areas can lead to compensatory patterns, such as overpronation, increased knee stress, and inefficient stride mechanics, all of which can contribute to injuries. Strengthening these muscle groups is crucial for optimizing power transfer, maintaining pelvic alignment, and absorbing impact effectively.Targeted exercises should focus on the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus, as well as hip flexors and abductors.

This comprehensive approach ensures that the entire hip complex is robust and capable of supporting the demands of running.Here are key exercises for hip and glute strength:

- Glute Bridges: A fundamental exercise for activating the glutes. Progress to single-leg glute bridges for increased challenge.

- Clamshells: Excellent for targeting the gluteus medius, responsible for hip abduction and pelvic stability. Use a resistance band around the thighs for added intensity.

- Lateral Band Walks (Monster Walks): These exercises effectively strengthen the hip abductors and external rotators, crucial for preventing knee valgus (knees collapsing inward).

- Lunges (various types): Forward, reverse, and lateral lunges engage the glutes, quadriceps, and hamstrings, promoting strength and balance.

- Squats (various types): Goblet squats, front squats, and Bulgarian split squats build overall lower body strength with a significant emphasis on the glutes and quads.

- Donkey Kicks and Fire Hydrants: These bodyweight exercises effectively isolate and strengthen the glutes and hip abductors.

The Importance of Flexibility and Mobility Work

While strength is essential, flexibility and mobility are equally vital components of a comprehensive return-to-running program. Flexibility refers to the ability of muscles to lengthen, while mobility refers to the range of motion at a joint. Together, they allow for a full, efficient range of motion during running, reduce muscle stiffness, and prevent compensatory movements that can lead to injury.Neglecting flexibility and mobility can result in tight muscles that restrict movement, leading to altered biomechanics and increased stress on joints and connective tissues.

Incorporating regular stretching and mobility exercises helps to maintain optimal joint function, improve muscle recovery, and enhance overall running performance.Key areas for flexibility and mobility work include:

- Hamstring Flexibility: Tight hamstrings can affect pelvic tilt and stride length. Gentle static stretches and dynamic movements are beneficial.

- Hip Flexor Mobility: Tight hip flexors, often from prolonged sitting, can lead to anterior pelvic tilt and lower back pain. Lunging stretches and hip flexor mobilization exercises are important.

- Calf Flexibility: Tight calf muscles can contribute to issues like plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinopathy. Calf stretches, both gastrocnemius and soleus, are recommended.

- Ankle Mobility: Good ankle dorsiflexion is crucial for proper gait mechanics. Ankle circles and calf stretches are helpful.

- Thoracic Spine Mobility: A mobile upper back allows for better arm swing and overall posture during running. Exercises like cat-cow and thread-the-needle can improve this.

Basic Strength Training Routine for Post-Injury Runners

This routine is designed as a starting point for runners returning from injury. It should be performed 2-3 times per week on non-running days, or with adequate rest between sessions and runs. Always listen to your body and consult with a physical therapist or healthcare provider for personalized modifications. Warm-up (5-10 minutes):

- Light cardio (e.g., brisk walking, cycling)

- Dynamic stretches (e.g., leg swings, arm circles, torso twists)

Strength Exercises (perform 2-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions for each exercise, unless otherwise noted):

| Exercise | Focus Area | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bodyweight Squats | Quadriceps, Glutes, Hamstrings | Focus on controlled descent and ascent. |

| Glute Bridges | Glutes, Hamstrings | Squeeze glutes at the top. |

| Lunges (alternating legs) | Quadriceps, Glutes, Hamstrings | Maintain a stable torso. |

| Plank | Core | Hold for 30-60 seconds. Focus on maintaining a straight line. |

| Side Plank (each side) | Obliques, Core | Hold for 20-40 seconds. |

| Bird-Dog | Core, Glutes, Back | Focus on slow, controlled movements. |

| Clamshells (with resistance band) | Gluteus Medius, Hip Abductors | Perform 15-20 repetitions. |

| Calf Raises | Calves | Perform on a flat surface or with the balls of your feet on a step for a greater range of motion. |

Cool-down (5-10 minutes):

- Static stretching (hold each stretch for 30 seconds): Hamstring stretch, quad stretch, calf stretch, hip flexor stretch.

Remember, consistency is key. As you progress, you can gradually increase repetitions, sets, or resistance, and introduce more challenging exercises under professional guidance.

Nutrition and Recovery Strategies

Returning to running after an injury requires a dedicated approach to fueling your body and facilitating its healing process. Proper nutrition and effective recovery techniques are paramount in supporting tissue repair, replenishing energy stores, and minimizing inflammation, all of which are crucial for a safe and successful return to your training routine.The body’s ability to heal and adapt is significantly influenced by what you consume and how you rest.

By prioritizing nutrient-dense foods and incorporating evidence-based recovery practices, you can optimize your physical readiness and reduce the risk of re-injury. This section will delve into the key components of nutrition and recovery that will aid your journey back to running.

Optimal Nutrition for Tissue Repair and Energy Levels

Adequate nutrient intake is the cornerstone of effective tissue repair and sustained energy. Your body needs specific building blocks and energy sources to mend damaged tissues and power your runs. Focusing on a balanced diet rich in macronutrients and micronutrients will significantly contribute to your recovery.Key nutritional considerations include:

- Protein: Essential for muscle repair and growth. Aim for lean sources such as chicken, fish, beans, lentils, tofu, and Greek yogurt. Distribute protein intake throughout the day, particularly after workouts.

- Complex Carbohydrates: Provide sustained energy for your runs and replenish glycogen stores. Opt for whole grains like oats, quinoa, brown rice, and sweet potatoes.

- Healthy Fats: Support hormone production and reduce inflammation. Include sources like avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil.

- Vitamins and Minerals: Crucial for various bodily functions, including immune support and tissue regeneration. Ensure a variety of fruits and vegetables in your diet. Pay special attention to:

- Vitamin C: Aids in collagen synthesis, a key component of connective tissues.

- Zinc: Plays a vital role in wound healing and cell growth.

- Calcium and Vitamin D: Important for bone health, especially if your injury involved bone stress.

“Adequate protein intake is vital for muscle protein synthesis, which is the process of repairing and rebuilding muscle tissue after exercise or injury.”

The Role of Hydration in Recovery

Staying well-hydrated is fundamental to nearly every physiological process, including recovery. Water is essential for transporting nutrients to cells, removing waste products, and regulating body temperature, all of which are critical for healing and performance.Proper hydration supports:

- Nutrient Transport: Water acts as a solvent, enabling the efficient delivery of proteins, carbohydrates, and micronutrients to injured tissues.

- Waste Removal: It helps flush out metabolic byproducts and inflammatory mediators that can impede the healing process.

- Joint Lubrication: Adequate fluid intake maintains the viscosity of synovial fluid, which lubricates joints and reduces friction.

- Thermoregulation: Crucial for maintaining optimal body temperature during exercise and recovery.

It is advisable to drink water consistently throughout the day, not just during or immediately after exercise. Monitoring urine color is a simple indicator of hydration status; pale yellow urine generally signifies good hydration.

Effective Recovery Techniques

Beyond nutrition and hydration, active recovery strategies play a significant role in promoting healing, reducing muscle soreness, and improving flexibility. These techniques help to manage the physical demands placed on your body as you gradually increase your running volume.

Stretching

Gentle stretching can help to restore muscle length and improve range of motion, which may have been compromised due to injury or inactivity. Focus on dynamic stretches before runs and static stretches after runs, holding each stretch for 20-30 seconds. Avoid overstretching, especially in the initial stages of return.

Foam Rolling

Self-myofascial release using a foam roller can help to alleviate muscle tightness and reduce trigger points. It can improve blood flow to the muscles and aid in the removal of metabolic waste. Target the major muscle groups used in running, such as the quadriceps, hamstrings, calves, and glutes. Roll slowly over tender areas, holding for 20-30 seconds.

Sleep

Sleep is arguably the most critical recovery tool. During deep sleep, the body releases growth hormone, which is essential for tissue repair and muscle growth. Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule and creating a relaxing bedtime routine can optimize sleep quality.

Managing Inflammation and Discomfort

Inflammation is a natural part of the healing process, but excessive or prolonged inflammation can hinder recovery and cause discomfort. Managing it effectively is key to progressing safely.Strategies for managing inflammation and discomfort include:

- RICE Protocol (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation): While rest is already discussed in the context of returning to running, ice can be applied for 15-20 minutes several times a day to reduce acute inflammation and pain. Compression can help minimize swelling, and elevation can also aid in reducing edema.

- Anti-inflammatory Foods: Incorporate foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids (fatty fish, flaxseeds, walnuts) and antioxidants (berries, leafy greens) into your diet, as they possess natural anti-inflammatory properties.

- Gradual Progression: Adhering strictly to your return-to-running plan and avoiding the temptation to do too much too soon is the most effective way to prevent exacerbating inflammation.

- Listen to Your Body: Pay close attention to any persistent or increasing pain. Discomfort is normal, but sharp, stabbing, or worsening pain is a signal to stop and reassess.

“The goal of recovery strategies is to facilitate the body’s natural healing processes, reduce the risk of re-injury, and prepare you for the next training session.”

Common Running Injuries and Specific Return Protocols

Returning to running after an injury is a delicate process, and understanding the nuances of common running ailments is paramount to a safe and successful comeback. Each injury presents unique challenges and requires a tailored approach to rehabilitation and return to activity. This section will explore some of the most frequent running injuries and Artikel specific considerations for safely resuming your training.Navigating the return-to-running journey requires an awareness of potential pitfalls and a proactive strategy to address them.

By understanding the characteristics of common running injuries, you can better anticipate the rehabilitation process, implement appropriate modifications, and know when professional medical advice is indispensable. This knowledge empowers you to make informed decisions and prioritize long-term running health.

Shin Splints (Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome)

Shin splints, characterized by pain along the inner edge of the shinbone, often stem from overuse and sudden increases in training intensity or volume. The return-to-running protocol for shin splints focuses on gradual reintroduction of impact and addressing underlying biomechanical issues.Key considerations for returning to running with shin splints include:

- Pain management: Ensure pain is minimal or absent before attempting to run.

- Surface selection: Begin on softer surfaces like grass or a track to reduce impact.

- Duration and intensity: Start with very short run/walk intervals (e.g., 1 minute run, 4 minutes walk) and gradually increase running time.

- Footwear: Ensure your running shoes are supportive and not worn out.

- Strength and flexibility: Incorporate calf raises, toe curls, and stretching of the calf and shin muscles.

Modifications for shin splints pain might involve reducing the frequency of runs, decreasing the duration of each run, and ensuring adequate rest days. If pain flares up during a run, immediately switch to walking or stop altogether.

Plantar Fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis involves inflammation of the plantar fascia, a thick band of tissue that runs across the bottom of your foot. Pain is typically felt in the heel and can be most severe with the first steps in the morning. A cautious and progressive return is crucial to avoid re-injury.When returning to running after plantar fasciitis, prioritize the following:

- Pain-free activity: Ensure daily activities, including walking, are pain-free before running.

- Stretching: Consistent stretching of the calf and plantar fascia is essential.

- Footwear: Wear supportive shoes with good arch support, even when not running.

- Gradual increase: Begin with short, slow runs, focusing on a smooth stride and avoiding pushing off forcefully with the toes.

- Cross-training: Continue low-impact activities like swimming or cycling to maintain fitness.

If you experience sharp or worsening heel pain during a run, stop immediately and reassess your readiness. Modifications may include reducing mileage, incorporating more walk breaks, and potentially using orthotic inserts.

Iliotibial Band (IT Band) Syndrome

IT band syndrome causes pain on the outside of the knee, often exacerbated by repetitive bending and straightening of the leg during running. The return strategy for this condition emphasizes addressing tightness in the IT band and surrounding muscles, as well as strengthening the hips and glutes.Specific return protocols for IT band syndrome include:

- Reducing inflammation: Initial rest, ice, and possibly anti-inflammatory medication may be necessary.

- Stretching and foam rolling: Regular foam rolling of the IT band, quadriceps, and glutes is vital.

- Hip and glute strengthening: Exercises like clamshells, glute bridges, and single-leg squats are crucial for stability.

- Gradual return: Start with short runs on flat terrain. Avoid hills initially.

- Listen to your body: If pain returns, reduce mileage or intensity, or take a break.

If pain persists or intensifies despite modifications, it is a strong indication that professional medical guidance is required. This may involve a physical therapist to assess biomechanics and provide targeted exercises.

Comparison of Return Strategies

While all return-to-running plans emphasize gradual progression and listening to your body, the specific focus areas can differ. For shin splints, the emphasis is on impact reduction and strengthening the lower leg muscles. Plantar fasciitis recovery requires diligent foot and calf stretching, alongside supportive footwear. IT band syndrome necessitates a significant focus on hip and gluteal strength to improve pelvic stability and reduce strain on the IT band.A common thread across all these injuries is the importance of cross-training.

Activities like swimming, cycling, or elliptical training allow you to maintain cardiovascular fitness without the repetitive impact of running, which is particularly beneficial during the initial stages of recovery for all these conditions.

The principle of “start low, go slow” is universally applicable when returning to running after any injury.

When Professional Medical Guidance is Crucial

While many minor running-related discomforts can be managed with self-care and a structured return plan, certain signs warrant immediate professional medical attention.

- Severe or sudden pain: Any sharp, intense pain that prevents you from bearing weight or performing daily activities should be evaluated by a healthcare professional.

- Pain that does not improve: If pain persists or worsens despite following a conservative return-to-running program for several weeks, seeking expert advice is essential.

- Signs of infection: Redness, swelling, warmth, or fever around the injured area may indicate an infection requiring medical intervention.

- Numbness or tingling: Persistent numbness or tingling can indicate nerve involvement and needs professional assessment.

- Suspected fracture: If you suspect a bone fracture, consult a doctor immediately for diagnosis and treatment.

For specific injuries like stress fractures, which can be a complication of undertreated shin splints or other overuse injuries, prompt medical evaluation is non-negotiable. Similarly, persistent IT band syndrome that doesn’t respond to conservative treatment may benefit from the expertise of a physical therapist who can identify and address underlying biomechanical imbalances. Runners experiencing chronic or debilitating plantar fasciitis may also require specialist input to rule out other conditions and receive targeted treatment.

Mental Preparation and Motivation

Returning to running after an injury is as much a mental journey as it is a physical one. Your mindset plays a crucial role in your recovery, adherence to your plan, and ultimately, your success in getting back to your pre-injury fitness level. This section focuses on equipping you with the psychological tools to navigate the challenges and stay motivated throughout your return.The process of returning to running can be daunting, and it’s natural to experience apprehension.

By proactively addressing these mental aspects, you can build resilience, maintain a positive outlook, and foster a sustainable relationship with running.

Overcoming the Fear of Re-injury

The fear of reinjury is a common and understandable concern for runners returning after an absence. This fear can manifest as hesitation, anxiety during runs, or an urge to push too hard too soon. Developing strategies to manage this fear is paramount for a successful and confident return.Several effective strategies can help mitigate the fear of re-injury:

- Gradual Progression: Adhering strictly to your return-to-running plan, which emphasizes slow and steady increases in duration and intensity, is the most potent antidote to re-injury fear. Each successful run builds confidence.

- Mindfulness and Body Awareness: Pay close attention to your body’s signals. Learn to differentiate between normal muscle fatigue and pain that indicates a potential problem. Practicing mindfulness during runs can help you stay present and connected to your physical sensations.

- Positive Self-Talk: Challenge negative thoughts and replace them with affirmations. Instead of thinking “What if I get hurt again?”, try “I am strong, my body is healing, and I am following my plan to return safely.”

- Visualization: Before a run, visualize yourself running smoothly, comfortably, and without pain. Imagine completing your planned distance and feeling strong and accomplished.

- Focus on What You Can Control: Concentrate on your preparation, your adherence to the plan, your recovery, and your effort during each run. External factors and the possibility of an unforeseen incident are largely beyond your control.

- Seek Professional Support: If the fear is significantly impacting your ability to run, consider speaking with a sports psychologist or therapist who can provide specialized coping mechanisms.

Setting Realistic Running Goals

Establishing achievable short-term and long-term goals provides direction, purpose, and a framework for measuring progress. Unrealistic goals can lead to frustration and demotivation, while well-defined, attainable goals foster a sense of accomplishment and encourage continued effort.A structured approach to goal setting is highly recommended:

- Short-Term Goals: These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART). Examples include:

- Completing a 10-minute run without pain by the end of week 2.

- Increasing running time by 2 minutes in each subsequent run this week.

- Attending all scheduled strength and conditioning sessions for the next 7 days.

- Long-Term Goals: These are broader aspirations that align with your ultimate return to running objectives. Examples include:

- Running a 5k race comfortably within 3 months.

- Returning to your pre-injury weekly mileage by 6 months.

- Participating in a specific race event in 9 months.

It is crucial to review and adjust these goals as your recovery progresses and you gain more confidence.

Motivational Techniques for Consistency

Maintaining motivation is key to sticking with your return-to-running plan, especially during periods of slower progress or when life’s demands interfere. Various techniques can help you stay engaged and committed.To sustain your motivation and adherence to the plan, consider implementing these strategies:

- Find Your “Why”: Reconnect with the reasons you love running. Is it for stress relief, fitness, social connection, or personal challenge? Reminding yourself of these core motivations can reignite your drive.

- Create a Running Routine: Integrate your runs into your daily or weekly schedule. Consistency breeds habit, and having a set time for running makes it less likely to be skipped.

- Find a Running Buddy or Group: Social support can be a powerful motivator. Running with others provides accountability, companionship, and a shared sense of purpose. Ensure they understand and respect your return-to-running plan.

- Vary Your Routes and Workouts: Prevent monotony by exploring new running paths or incorporating different types of running (e.g., short, easy jogs) as your plan allows.

- Reward Yourself: Acknowledge your achievements with small, non-running-related rewards. This could be a new book, a massage, or a healthy treat after successfully completing a week of your plan.

- Listen to Music or Podcasts: Engaging audio content can make your runs more enjoyable and help you pass the time, especially during longer durations.

Managing Frustration with Slower Progress

It is not uncommon for recovery and progress to be non-linear. You may encounter days or weeks where you feel you are not advancing as quickly as you’d hoped. Managing frustration during these times is essential to prevent discouragement and potential setbacks.When progress feels slower than anticipated, employ these approaches:

- Acknowledge and Validate: It’s okay to feel frustrated. Recognize these feelings without judgment. Understand that setbacks are a normal part of the healing process.

- Revisit Your Plan and Goals: Sometimes, frustration arises from a disconnect between expectations and reality. Review your original goals and your current plan. Are they still realistic? Do they need minor adjustments?

- Focus on Non-Running Progress: Recognize improvements in other areas. Are you sleeping better? Is your mood improved? Is your strength and flexibility increasing? These are all valuable indicators of progress.

- Seek Perspective: Talk to your physical therapist, coach, or a fellow runner who has experienced a similar recovery. Hearing about their experiences can provide valuable perspective and reassurance.

- Practice Gratitude: Shift your focus to what you have achieved rather than what you haven’t. Be grateful for the ability to run again, even if it’s just for a short duration.

Tracking Progress and Celebrating Milestones

A system for tracking your progress and acknowledging your achievements is vital for maintaining motivation and a clear understanding of your journey. It provides tangible evidence of your hard work and reinforces positive behavior.Implement a robust system for tracking and celebrating:

- Running Log: Maintain a detailed log that includes the date, duration of run, distance (if applicable), perceived exertion level, any pain or discomfort experienced, and how you felt afterward. This can be a physical notebook or a digital app.

- Symptom Tracker: Alongside your running log, keep track of any pain or discomfort related to your injury. Note its intensity, location, and what activities aggravate or alleviate it.

- Strength and Conditioning Log: Record your exercises, sets, reps, and weights used for your strength training sessions. This helps monitor your progress in building supporting muscle strength.

- Milestone Identification: Define what constitutes a milestone for you. This could be running continuously for 20 minutes, completing a week without pain, or reaching a certain distance.

- Celebration Methods: Plan how you will celebrate these milestones. This could be a special meal, a new piece of running gear, a massage, or simply taking a day to relax and enjoy your accomplishment.

Tracking your progress not only provides a record of your journey but also offers valuable data that can be shared with your healthcare provider to inform future treatment and training decisions.

Equipment and Gear Considerations

Navigating the path back to running after an injury involves more than just physical rehabilitation; it also requires careful attention to the equipment and gear that support your efforts. The right tools can significantly enhance your safety, comfort, and overall recovery process.The selection and condition of your running gear play a crucial role in minimizing stress on your recovering body and preventing re-injury.

Investing time in understanding these considerations can make a substantial difference in your return-to-running journey.

Running Shoe Selection and Suitability

Proper running shoe selection is paramount when returning to running after an injury. Shoes provide the primary interface between your feet and the ground, absorbing impact and influencing your biomechanics. For an injured runner, the right shoe can offer enhanced cushioning, stability, or support, depending on the nature of the injury, thereby reducing stress on the affected area. Conversely, worn-out or inappropriate shoes can exacerbate existing issues or contribute to new ones.Assessing the suitability of your current running shoes is a critical step.

Several indicators suggest it might be time for a new pair:

- Wear Patterns: Examine the outsoles for uneven wear, particularly in the heel or forefoot, which can signal biomechanical issues or that the cushioning has compressed unevenly.

- Cushioning Compression: Press down on the midsole. If it feels hard, rigid, or you can easily feel the ground through it, the shock-absorbing properties have likely diminished significantly.

- Outsole Tread: A lack of visible tread pattern, especially in key areas, means the shoes have lost their grip and their ability to provide the intended support.

- Upper Material: Look for tears, holes, or stretching in the mesh or fabric, which can indicate a loss of structural integrity and support.

- Mileage: While subjective, most running shoes are designed to last between 300-500 miles. If you’ve exceeded this range, even if they look okay, their cushioning and support are likely compromised.

- Discomfort: If your shoes have started causing new aches or pains, or if your previous injury feels aggravated when wearing them, they are no longer suitable.

When purchasing new shoes, consider visiting a specialized running store. Staff there can analyze your gait, discuss your injury history, and recommend shoes that offer the specific support and cushioning needed for your recovery.

Supportive Gear Integration

Beyond shoes, other supportive gear can be beneficial, provided it is recommended by a healthcare professional or physical therapist. These items are designed to offer targeted assistance and compression.

- Compression Socks: These can improve blood circulation, which aids in reducing swelling and muscle fatigue. For some, they also provide a proprioceptive feedback that can enhance awareness of the leg and foot position, potentially leading to better form.

- Ankle Braces or Sleeves: For injuries involving the ankle or foot, a brace or sleeve can offer external stability and support, helping to prevent excessive movement that could re-injure the area. It’s crucial to use these as advised, as over-reliance can sometimes weaken supporting muscles.

- Orthotics: Custom or over-the-counter orthotics can correct biomechanical issues by providing arch support or altering foot alignment, which may be crucial for certain types of injuries.

It is important to use these aids judiciously and as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation plan, rather than as a sole solution.

Monitoring Progress with Technology

Leveraging technology can be an invaluable asset when returning to running. A running watch or a smartphone app can help you meticulously track your progress, ensuring you adhere to your gradual return-to-running plan.

- Pace Monitoring: Maintaining a controlled and easy pace is vital during the initial stages of return. A watch or app allows you to monitor your current pace, helping you avoid pushing too hard too soon. This prevents overloading your injured tissues.

- Distance Tracking: Similarly, keeping track of the distance covered ensures you are gradually increasing your load without overwhelming your body. This systematic progression is key to building endurance safely.

- Heart Rate Monitoring: For some, monitoring heart rate can provide an objective measure of effort, ensuring you are running within your aerobic zones and not exceeding your body’s current capacity.

- GPS Data: This can help you map out your routes, ensuring consistency and allowing you to replicate successful runs or identify areas that might be too challenging (e.g., steep hills).

By providing objective data, these tools help remove guesswork and allow you to make informed decisions about your training, fostering confidence and adherence to your recovery plan.

Environmental Factors for Outdoor Running

As you progress to outdoor running, considering the environment becomes increasingly important. The surface you run on and external conditions can significantly impact your body and the demands placed upon it.

- Surface Type: Varying running surfaces can distribute impact differently. Softer surfaces like trails or grass might be gentler on joints than hard concrete or asphalt, especially in the early stages of return. However, uneven trails can also pose a risk of twists or falls, so assess your stability and confidence on such terrain.

- Terrain Inclination: Steep inclines or declines can place additional stress on certain muscle groups and joints. Initially, opt for flatter routes to minimize this added strain.

- Weather Conditions: Extreme heat or cold can affect your body’s performance and recovery. Dehydration is a risk in hot weather, while cold can make muscles stiffer. Ensure you are appropriately dressed and hydrated for the conditions.

- Lighting: When running in low light conditions, visibility is crucial for safety. Ensure you can see potential hazards on the path and that you are visible to others, especially if running near roads.

Epilogue

In essence, returning to running after an injury is a journey that demands patience, knowledge, and a commitment to a well-defined strategy. By embracing a gradual approach, prioritizing strength and conditioning, and paying close attention to nutrition and recovery, you can significantly reduce the risk of re-injury and build a more resilient running foundation. Remember to listen to your body, celebrate your progress, and approach your return with both determination and a healthy dose of self-compassion.

Your successful comeback awaits.